Saturday, August 23, 2014

The Greatest Film I've Ever Seen

The following is a post I wrote several years ago when I was a regular contributor to Edward's Copeland's Tangents. I am re-posting it here for the Spielberg Blog-a-thon (hosted by Kellee of Outspoken & Freckled and Michael of It Rains, You Get Wet) because I still stand by it.

The phrase "I know it when I see it," uttered by Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart regarding pornography, is an expression that, at one time or another, we've probably all heard used to encapsulate the frustration of failing to define something whose basic nature seems otherwise unexplainable. I mention it only because I've been wondering lately if art isn't also like that. It is nigh impossible to define and/or analyze a great work of art to such a degree that the elements that make it timeless and brilliant can be adequately determined, nor a basic "formula" be found. It's like the color yellow. You can't really define it. You have to just point at it and say, "See that? That's it." When I think of some of the works of art that I consider to be among the greatest ever created — Shakespeare's Hamlet, Mozart's "Requiem," Vermeer's "Girl With a Pearl Earring" — I find myself struggling to find the proper words to capture their greatness. In the end, I can't really articulate what makes them great. I have to just point it out to others and see who "gets it" and who doesn't. Well, this piece that I am writing for the "Spielberg Blog-a-thon" is about a film that I think falls into that category.

To be clear, I realize how absurd it is for any individual to declare a particular film the "greatest ever made," because there's just no way that anybody can possibly know that (unless maybe they've seen every film ever made...which, of course, nobody has). However, I do think that a person can make a definitive statement about the greatest film that he/she has ever seen (based on whatever criteria he/she wishes to use). Nevertheless, you would be hard-pressed to find a cinephile who's willing to commit to such a monumental claim (the most you might get out of them is their personal "favorite" film, but even that is rare). Why is this? Well, my theory is twofold: first off, they know that their pick could change with the very next film they watch and secondly, they are well-aware of the fact that it's really just a subjective opinion which says more about them than it does about the film itself. I myself possessed this reluctance for the longest time. Whenever I was asked what my favorite film was (or, even more rarely, what was the best film I'd ever seen), I hemmed and hawed for a while, throwing out several disclaimers and mentioning a list of about eight or nine films that could qualify for that honor.

Over the years, though, I have found myself returning to one film over and over again: the film that had a profound impact on its director, on the culture at large and on me personally (as a cinephile certainly but also as a human being). It was the film I held up as the standard by which to measure all other films. It was the film I thought of whenever anyone spoke of "cinematic high art" or how the motion picture medium could achieve its true potential. I would discover new and profound truths contained within its frames every time I watched it. Far from diminishing in quality with each viewing, it actually improved in my eyes. I finally had to admit the truth to myself. This is the greatest film I've ever seen and probably ever will see.

It's Steven Spielberg's masterpiece Schindler's List.

I first heard of Spielberg's "Holocaust flick" in the summer of 1993 when I was reading an issue of Entertainment Weekly. I was flipping through their "Winter Movie Preview" section when I turned the page and saw the photograph seen below of Liam Neeson as Oskar Schindler addressing "his" Jews staring back at me. I knew who Spielberg was because I had grown up with E.T. and the Indiana Jones adventures and had only recently become interested in him again because of the movies Hook and Jurassic Park. Like a lot of people at the time, my reaction was one of confusion and skepticism. This did not seem like the kind of film that Spielberg was typically known for. Could he pull it off or would it be a failure on a massive scale? I was curious to say the least.

When the film was eventually released during the winter of my senior year in high school, I went with my dad to the movie theater on Ninth Street in Corvallis, Ore. to see it. I wasn't entirely sure what to expect. I knew the film was going to be serious. I knew it was going to be heavy and, not least of all, I knew it was going to be very violent, but I also had a sense that it was going to be worth seeing. I didn't realize it at the time, but I was at a crucial point in my development as a cinephile. I had always loved movies, but I approached them primarily as a form of entertainment. The idea that they could also function as a means of artistic expression was a concept I was only beginning to become vaguely familiar with (prompted especially by a film history class, led by my good friend Tucker Teague, which I had recently attended). Needless to say, I was also moving rapidly toward a major crossroad in everyone's life. I was 17 years old. Graduation was just around the corner and I was preparing to leave home and head off to college to try and figure out who I was and make something of myself. All this served as the context for my introduction to the film and may even help to partially explain why the film had such a big impact on me.

When the lights went down and the movie started, I was actually bewildered at first because I had understood that the entire film was in black-and-white. What I was seeing was in color. A hand was striking a match and lighting some candles. A Jewish family was gathered around a table in a small room celebrating the Sabbath. The patriarch was singing something in a language I didn't understand. Was this a mistake? Were my dad and I in the wrong movie? Soon the family faded from the scene (though the song/prayer could still be heard) but the candles were left behind. As one shot dissolved into the next, clearly signifying the passing of time, the candles burned further and further down (this also was when the main title appeared on the screen indicating to me that this was indeed Schindler's List, though I was still somewhat confused). Finally, the camera showed only a solitary candle with the flame about to burn itself out. I didn't notice it then but the candle and the background were already in black and white. Only the tiny flicker of flame was still in color. The flame soon extinguished and the resulting thin streak of smoke that flowed upward from it was followed by the camera. A train whistle was suddenly heard and the movie cut to a cloud of thick, gray smoke that poured forth from the smokestack of a locomotive. Now the film was completely in black-and-white and I knew I was in the right movie.

The greatest films have openings that are unforgettable. The Godfather has that wonderfully slow zoom-out with the heartbroken father seated in a dark room relaying his tale of woe to a mysterious figure ("I believe in America."). Citizen Kane has the magnificent montage of shots of that fortress Xanadu which culminates in a single whispered word ("Rosebud.") and a shattered snow globe. Schindler's List has the sequence I just described. There is so much going on just in that brief collection of sounds and images (Spielberg's symbolic use of color and its lack thereof, the imagery of the candles being snuffed out and the ensuing smoke, etc) that I could write the rest of my piece on it alone. Suffice it to say that from that opening, I already was engaged by the film. Indeed, I was captivated and that sensation never let up for the next three hours and 14 minutes (during which I wept a couple times). When it was completely over and the lights came up I noticed that most of the people who were in the theater with us also were still sitting there, dumbfounded. We all looked like we'd been sucker-punched. Slowly and silently, everyone started to get up and walk out including my father and I. As we often do, we talked about the movie in the car, though I don't remember much of what we discussed. What I do remember is his taking me by Fred Meyer on the way home and purchasing the film's soundtrack for me because among the many things that stood out to both of us was John Williams' sad, but achingly beautiful, musical score.

Like a lot of folks, my initial reaction to the film was one of shock. I was horrified by what I had seen on screen. I was shaken to the core of my being and consequently couldn't revisit the film for a long time afterward. I just knew that I loved it. It reached me in a way that very few films can or do. I also remember thinking that this was a different kind of movie than most of the other films I had seen...not just in terms of content but in terms of style. My clumsy way of characterizing it back then was to say that it felt "like a foreign film only it was in English; it didn't feel like a Hollywood movie at all." I was also astounded that it had been directed by the same man who was responsible for the movie I had seen only six months earlier that featured giant dinosaurs eating people. "This is not the same man. This can't be the same man," I thought to myself. Nowadays when I watch the film (having in the interim become far more familiar with the subtleties and nuances of Spielberg's general technique), naturally I can see his hand in the execution of this story, but in a sense I was right in my initial reaction. Schindler's List was not helmed by the same Spielberg who did Jaws, E.T. or even his previous serious efforts such as The Color Purple and Empire of the Sun. Schindler represented a major challenge for Spielberg. In bringing this story to the screen, he pushed himself in a way that very few filmmakers ever do. He did so not only technically but emotionally and spiritually as well. He re-connected with something in himself that he had denied for a very long time: his own Judaism. Making Schindler's List changed Steven Spielberg just as watching it changed me.

Although controversy has always surrounded Schindler's List, I myself wasn't aware of most of it upon its release. All I heard was praise for the film. This was probably just as well since my passionate love for the film would've blinded me to anything negative anyone would've said about it. As the years have gone on, and I've watched it numerous more times as well as familiarized myself with the various writings on it, I feel I am in a better position to understand and appreciate the problems that people have with it (David Mamet famously called it "emotional pornography"). I could acknowledge that Schindler's List may not be a "perfect" film (if such a thing even exists), but as the great Pauline Kael (who, incidentally, did not care for the film) once said, "Great movies are rarely perfect movies." There may be legitimate criticisms of Schindler's List, but they are not significant enough to undermine the overall greatness of the finished product. If Schindler missteps occasionally it does so because it reaches higher than most other films dare to. I've long thought it's better to strive for greatness and "fail" than aim for mediocrity and succeed.

I could talk at some length about the true story that the film represents, but by this point everyone already knows it. I could also go on and on about how impressive the film is in all of its technical areas (the stunning cinematography by Janusz Kaminski, the aforementioned music score by John Williams, the impeccable screenplay by Steven Zaillian, the striking editing by Michael Kahn, the excellent performances by all of the actors, etc) but since this piece is already getting too long I am going to conclude by attempting to explain not only why the film means so much to me personally but why I feel it belongs in the pantheon of the greatest art ever fashioned by humans. To those who have heard me expound on this subject before, some of this might sound a little familiar.

Schindler's List is more than just a Holocaust movie. Like all great works of art it transcends its subject matter. It is a meditation on the extremes to which we human beings can go. Not only is its depiction of human darkness, brutality and evil (as personified by the psychotic Nazi officer Amon Goeth) the most honest I have ever seen, but its portrayal of human goodness, courage and nobility (as represented in the complex, but ultimately righteous, person of Oskar Schindler) is the most compelling I have ever experienced. Rarely does a film so successfully highlight both the best and worst of humanity simultaneously. Like most Holocaust movies it doesn't shy away from showing the cruelty and inhumanity of the atrocities that the Nazis inflicted, but it also dares to depict the love, mercy and compassion that many exercised in the midst of so much bleakness and tragedy. Schindler's List not only opened my eyes to what cinema is capable of (particularly in how it can dramatize a serious subject with passion and dignity while still reaching a massive audience), but it also made me want to be a better human being (how many films can you say that about?). As I told someone recently, I would rather be inspired by goodness than merely repulsed by evil. Schindler's List does both. Like the film's opening sequence, it is more about lighting a candle than cursing the darkness.

Wednesday, August 13, 2014

Turtles on Steroids

I've been mildly curious, though extremely skeptical, since I heard of the new Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles movie (and despite my vow never again to watch another Michael Bay-directed film, the fact that he merely produced this one provided a convenient loophole). I was in Jr. High when they first became huge, so I was the perfect age to be into them (although I remember my first introduction was in fifth grade when my comic book fanatic friend Merlin Carson showed me a role-playing game book cover and based on the title alone I was incredulous; "This will never catch on," I actually said). The film's miserable critical reception -- 20% on rottentomatoes -- almost dissuaded me, but if there's anything I learned from last summer's Lone Ranger, it's that if a movie looks at all interesting to you, even if it is universally reviled, you should see it and decide for yourself. So, I saw and it and I decided for myself.

Probably the best thing to be said for this new TMNT is that it is not nearly the disaster it could have been. It is, for the most part, pretty harmless junk, neither offending nor engaging. Brad Keefe said, "It isn't nearly as bad as it could have been. Mind you, it isn't good. It isn't even 'so bad it's good.' It's just there. I wish it was better. Or worse." Well, I don't necessarily wish it was worse, but I can sympathize with his indifference.

Naturally I still have my issues. I don't like the design of these new turtles. First off, I could never really get over their new nostrils. They just bug me. Secondly, in trying to make them appear "cooler" to today's audiences, the filmmakers have adorned their bodies/shells with perepheranlai (sunglasses, necklaces, etc) making them look like a cross between military grunts and homeless people. The cobbled-together nature of it makes a kind of sense I guess, but it ends up just looking cluttered. I miss the sleekness and simplicity of the characters' looks from the old cartoon and movies (where they were distinguished only by their weapons and the color of their masks). The surfer-speak has been understandably dropped (though replaced with a hip-hop/gangta lingo) and the turtles have also been made taller and more muscular. These are more intense, agressive incarnations of these characters. Grittier and edgier heroes in a halfshell for a darker, more cynical youth. At least they got their personalities and inter-relationships right. Leonardo is still the leader and constantly butting heads with the rebellious Raphael. Donatello is still the techno-geek and Michelangelo the laid-back one. My favorite moments were probably when the turtles had to work together, the themes of family loyalty and teamwork having always been one of the most appealing elements of these stories for me. I also liked the elevator gag.

The non-reptilian characters in this whole affair are pretty forgettable. Nowhere is there a human with the charisma and screen presence of Judith Hoag or Elias Koteas. The always reliable William Fichtner (who was also in Lone Ranger) comes the closest to actually being interesting. Whoopi Goldberg and Will Arnett are wasted while Megan Fox -- and I realize this is not exactly breaking news -- is really a bad actress and embarrasses herself in just about every scene. The turtles' nemesis, the Shredder, is barely a human character as he spends most of the film in his now bulked-up, servo-assisted suit (which eerily resembles the Silver Samurai from last year's Wolverine) and becomes fully CGI as soon as he starts fighting in a wildly animated manner. This is typical of the kind of excess displayed in a film that thinks more is better. Everything is on steroids.

With one exception, the action sequences are fairly ho-hum, although director Jonathan Liebseman seems to possess a bit more of an appreciation for spatial coherence than his producer. The one scene I found enjoyable and, dare I say it, even a bit exciting was the chase down the snowy mountainside.

Finally, while they wisely abandoned the lame alien idea (there is even a line of dialogue in the film acknowledging so), their changes to the backstory are not exactly improvements. The turtles and Splinter (voiced here by Tony Shalhoub) are now subjects in a mutation experiment who were saved from a laboratory fire by a young April O'Neil and dumped down a sewer. This sacrifices one of the aspects of the turtles' origin story I always liked (and demonstrates a growing trend in superhero/comic book adaptations that I don't like): namely, the seeming randomness of their genesis. Like the rebooted Spider-man franchise (from which this movie basically steals its plot/climax), the turtles are no longer just victims of circumstances whose transformations result from a freak accident (they stumbled on a broken cannister leaking a radioactive ooze). Call me nit-picky, but I miss the days when heroes were created through chance. I don't want Peter Parker to be the only guy who, through genetic pre-determination, could possibly have become Spider-man. I want his being bitten by the super-spider to be a coincidence and his decision of how to use his newfound powers to be what makes him a hero. That is more compelling to me. Same with Batman. I've always preferred the idea that Bruce Wayne's parents were gunned down by some anonymous hood who disappears rather than them being assassinated as part of a big conspiracy. What happened to the days when an ordinary schmoe (or turtle) was just in the wrong place at the wrong time and was struck by lightning or hit by a meteorite or encountered toxic waste or survived an explosion or something? Why do their heroic births always have to result from design now (I mean, obviously from a storyteller's perspective it's by design, but I am talking about within the universe of the story itself)? I miss those days.

Oh, and rather than being the pet of a Chinese master from whom he learns the martial arts, Splinter teaches himself ninjitsu from an abandoned book and passes the knowledge on to his "sons." I know expecting realism is futile in a movie featuring six-foot talking turtles, but that just struck me as really stupid and lazy.

In the end, I didn't hate this Turtles, even thought it is mostly devoid of the charm and self-awareness that made most previous incarnations amusing... especially the live-action 1990 film (featuring those remarkable suits designed by Jim Henson's creature shop) which for my money is still the best Turtles movie to date. The kids in the theatre where I saw this one, however, seemed to like it. Cowabunga, dude.

Wednesday, June 18, 2014

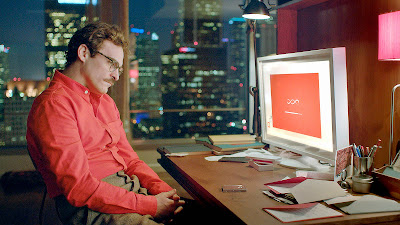

Me and HER

Most people don't know this about me -- not because I've made a secret of it (I'm not ashamed or embarrassed or anything like that; it's certainly not the stigma that it used to be), it just rarely comes up -- but I met my wife online.

It wasn't through eharmony or some other dating website, but through the Internet Movie Database. That's right. Years ago when I worked at the video store in Oregon, I spent a lot of time on the IMDB message boards discussing movies with total strangers. Amidst all the various conversations, Kristin and I each found the other fun and interesting. We became Myspace friends (that's how long ago this was), corresponded individually and subsequently graduated to talking on the phone. Eventually we became really good friends (chatting sometimes for up to eight hours straight). I looked forward to receiving a private message from her or hearing my phone ring and knowing it was her. After several years of this, the big step came when I flew out to Indiana where she was attending school and spent a week with her. It was a great week and it cemented something that I had known already for a while... I loved her. Somewhere along the way I fell in love with her (and she with me, thankfully) and within a couple years of that trip we were married and have been ever since. We'll be celebrating five years this August.

I mention my unusual courtship to illustrate that I am only too familiar with the phenomenon of being attracted to someone without ever actually having met them in person. I had a few photos of Kristin but otherwise she was a personality without a body, a voice over the phone, a collection of words on a screen... and yet I still loved her. After we became a couple we still had to stay separated for months at a time as we lived 2,000 miles apart, so our interactions over the phone became the sum and substance of our relationship. We did things "together" (watching the same movie on DVD simultaneously, going for a walk somewhere, etc) but, aside from a weekend every few months where one of us would fly out to see the other, we never occupied the same physical space.

It is for this reason that the movie Her hits uncomfortably close to home for me.

For those who may not already know, Spike Jonze's Her takes place in a near (and very plausible) future society where technology has become so advanced that it has drained much of the humanity out of humankind. It is a world both stunningly beautiful and eerily cold. Filmed in Shanghai, the architecture is amazing (and gorgeously rendered by the superb cinematography of Let the Right One In's Hoyt Van Hoytema) but it's sterile. There is no garbage, seemingly no crime, no hint of the messiness of our common everyday experience and, I must admit, having seen so many dystopian futures in movies, it's a refreshing change (visually the film resembles Andrew Niccol's GATTACA, but with a completely different ominous underbelly). Amongst these flawless towers of glass and concrete, a mass of human beings move in and out, completely isolated from one another. I noticed that in every crowd shot, although we have no sound, people's lips are constantly moving indicating that they are dictating something, talking to another person or, as we will later see, interacting with their operating systems. The story of Her could easily be told -- with very little alteration -- about any one of these people, but it chooses to focus on Theodore (no last name) played by a sweet but pathetic Joquain Phoenix. Theodore is a very sensitive yet socially awkward man who works for an organization that composes hand-written letters on behalf of other people (the term "hand-written" being a misnomer since they are printed on a computer and simply designed to look inscribed... which, of course, is consistent with one of the film's main themes about simulation replacing reality). Theodore's letters are among the company's most emotional and heartfelt, but his love life outside of work is a wreck as he is in the process of divorcing his wife of many years. Theodore purchases a newly invented operating system that is actually sentient (a "female" entity that dubs herself Samantha and who sounds a lot like Scarlett Johanssen) and soon forms an attachment to it/her. Interestingly, that attachment is returned by Samantha and soon love blossoms between them. However, as I learned myself from falling in love with a disembodied voice, difficulty soon follows as both members become dissatisfied with the nature of the relationship and want... more.

The conceit is a simple but brilliant one. Similar concepts have been explored before but in my experience not with quite the same brutal honesty and startling vulnerability that Her does. Some have likened it to Michel Gondry's Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (another melancholy sci-fi love story) and the comparison is apt, but I was actually reminded more of a different film, a strange but soulful little work called Lars and the Real Girl where Ryan Gosling plays another sensitive but awkward loner who forms a "relationship" with a blow-up doll and his whole community, out of sympathy for him, participates in the act. Both films focus on unusual romances between lonely men and the objects (and I emphasize the word objects) of their affection. Both premises seem like potential fodder for some pretty outrageous comedy but in fact neither film is especially funny... nor is trying to be. Although they certainly have their moments (one such sequence being Theodore's phone sex encounter with a bizarrely disturbed woman -- hilariously voiced by Kristen Wiig -- early in the film*), their general tone instead is one of sadness. They seem to be lamenting the absurd lengths to which human beings will go to simply form some kind of a "connection" that feels meaningful and they are posing the question of whether such connections are even possible the more reliant upon technology we become (i.e. as things move further away from the real and toward the virtual).

(*Note: The disastrous phone sex sequence is contrasted by a later scene where Theodore has sex with Samantha and it is a much sweeter, more intimate encounter. Jonze signals the difference by cutting to a black screen as we simply hear Theodore and Samantha "copulating." It both respects the characters (giving them their "privacy") and also equalizes them in that they both become mere voices in that moment.)

I should probably confess up front that outside of that amusing Siri commercial with Marty Scorsese ("Is that Rick.....? Where's Rick?" "*HERE'S RICK.*" "Nah, that's not Rick."), I know virtually nothing about anthropomorphized operating systems. That probably makes me the ideal audience for this film as I have friends in computer programming who have serious issues with it. In my mind the verisimilitude of the artificially intelligent OS is somewhat beside the point. The OS essentially serves as a metaphor, a placeholder for whatever entity we decide to invest ourselves in emotionally. It may require more imagination at certain times, but I was surprised at how much Her suggests the activity of loving someone/thing takes place in our own heads. While watching it I was reminded of the Scottish philosopher David Hume who held that we are unable to make direct contact with (and therefore have no actual knowledge of) reality but we can only make contact with our own ideas (which are derived from impressions formed by sense perception). I began to wonder the same thing about love. When we love someone, are we really loving them or are we just loving the idea of them that exists in our own mind? If the latter, then the degree to which my version of them corresponds to the actual them depends on how much I am willing to change myself to accommodate them. A film like Her manifests that question in an exaggerated but very provocative way.

Of course, none of these ambitions would mean anything if the film weren't splendidly produced. Spike Jonze's thoughtful writing and confident direction, the aforementioned visuals, the performances by the actors (both Phoenix and Johanssen do phenomenal work) and the bittersweet music score are all top shelf and make the movie's ideas all that more potent.

Although it took me well into the next year before I saw it, I am tempted to agree with those who call Her the best picture of 2013 (my previous pick being Rick Linklater's Before Midnight, another film about the various difficulties in long-term relationships). I was pleasantly surprised at how much it took the various positives and negatives associated with love (the joys, the miseries, the pettiness, the selfishness, the neuroses, the sacrifices, etc) and put them on the screen in an extremely powerful and evocative way. It made me uncomfortable at times. It was unsettling, but it was a very revealing look at human nature and, not least of all, it made me very grateful for the love I do have in my own life... at least, I think I love my wife. I don't think that I love only the "idea" of her that I've created in my own mind, an idea that first formed back when she was just an anonymous poster on IMDb and which got a bit more nuanced as she became a voice on the phone and eventually a flesh-and-blood person I could hang out with. Maybe I don't actually love Kristin. Maybe I am just, in a way, loving myself.

*thinks for a moment*

No, I think Hume was wrong. I don't love the idea of my wife. I love her... and I loved Her.

Tuesday, April 22, 2014

A Born Loser

The Coen brothers love losers.

I can't believe it took me this long to figure that out, but the Coens clearly have a soft spot in their hearts for individuals who try desperately to achieve success and yet fail. Barton Fink, Larry Gopnik, Ed Crane and even Sheriff Tommy Lee Jones... all characters who reached for something and yet fell short of their goal. Occasionally they make a movie about a "loser" who actually wins (Hudsucker Proxy, True Grit, O Brother Where Art Thou, etc) but those seem to be the exception rather than the rule and oftentimes their accomplishment comes more from luck than from their own ingenuity, skill or intelligence. In a cinematic landscape filled with protagonists who defy all odds to win the day, the Coens' focus on those who end up with the short end of the stick is rather refreshing.

Llewyn Davis is the latest in a long line of Coen losers. He navigates New York's 1960's folk music scene trying to break through but never quite getting there. It's not because he's bad. Indeed he's quite good and we get many opportunities to see him play (the film could almost be considered a musical), but for whatever reason fame and recognition elude him. Is it cosmic justice for the numerous poor decisions he makes along the way (sleeping with his friend's wife, antagonizing his few friends, behaving selfishly and acting just generally self-destructive; in many ways he's his own worst enemy) or is it just bad luck? You don't get discovered but the guy who goes onstage after you becomes a huge sensation (just as some lost cats find their way home and others just wander the wilderness). The movie never tells us.

I love the Coen brothers and I loved Inside Llewyn Davis. It is, like all of their films, impeccably constructed with some great images (the look of the film has a subtle, melancholy beauty), colorful characters played perfectly by a fine cast, fantastic music (yet another soundtrack I'm going to gave to buy) and some truly hilarious moments. While not perhaps their best film (although lately I find ranking there movies a virtually impossible task), I'd dare say it's one of the best films of 2013.

That's what I got.

Saturday, February 22, 2014

Robo-Robocop

One's ability to enjoy Jose Padhila's re-imagining of Robocop will probably be in direct proportion to how well one can forget the original. It is not a bad film by any means, and compared to the string of recent remakes, reboots and relaunches, it is probably near the top of the heap, but when put next to Verhoeven's sharp, satirical and eerily prophetic 1987 masterpiece, it is inferior in almost every way.

The plot, in broad terms, is essentially the same: in the near future, tough Detroit cop Alex Murphy is killed/critically injured, given a second chance at "life" as a cyborg police officer and eventually undergoes an existential identity crisis as he takes on the corrupt corporation that built him. It is in the particulars that the film establishes its differences: Murphy's wife and son play a much bigger role this time around, the suit's new design -- obviously influenced by the Iron Man franchise -- is sleeker and a somewhat dull all-black rather than the bulky shiny chrome of the original, the story still stops occasionally for media/exposition breaks (though rather than a news broadcast we are treated to amusing talk show clips with an alarmist Bill O'Reilly-like host) and while the first one dealt with issues relevant to the 80's (the rise of corporate America, the privatization of public institutions, the militarization of the police, the slow bleeding of our nation's economic resources, etc), this one, while still tackling some of the same issues, emphasizes more contemporary concerns (drone warfare, America's foreign policy, big brother-like surveillance, the increasingly blurred line between human beings and technology, etc). The whole thing is intelligently and competently done. All of the elements are in their proper place, but the whole enterprise feels... well, mechanical. While the first Robocop was infused with a thorough (and at times surprisingly moving) humanity, this Robocop so often feels like it is, much like the protagonist at various points in the story, on auto-pilot. It moves along at a relatively brisk pace but still seems to lack the energy or conviction of its predecessor. I found it holding my attention without really engaging me emotionally. The CGI, like all modern Hollywood movies, vacillates between very good and extremely cartoonish and the action is diverting without being especially thrilling (which is ironic given that this Robocop can both run and jump rather than just lumber along slowly like the original did).

What it's also missing, unfortunately, is the original's wicked sense of humor. Verhoeven's film was not only provocative in its socio-political observations and highly astute in its criticism of American culture, it was also REALLY damn funny. I kept waiting for a sequence with the biting hilarity of the original's Ed-209 eviscerating a hapless executive in a board meeting demonstration gone wrong. In fact, the film in general is pretty sanitized (one could even say "neutered"), drained not only of its namesake's extreme violence but also of its wild and unpredictable, but not incoherent, shifts in tone. This Robocop is very "safe" and "middle-of the-road" and it is reflected in its family--friendly PG-13 rating (whereas the original was forced to make cuts to receive an R instead of a dreaded X)

The cast is good: old Commissioner Gordon Gary Oldman and even older Batman Michael Keaton play the ying and yang of Omnicorp (the company that creates Robocop) and both are very effective. It's nice to see Keaton in a major movie again -- he reminds you of his ability to play a convincing, but not cliched "mustache-twirling" villain -- while Oldman brings nuance and complexity to his more sympathetic role of the Dr. Frankenstein to Robo's "monster." Jennifer Ehle, Jackie Earl Haley, Marianne Jean Baptiste and Samuel L. Jackson (a bit more restrained than I would like to have seen him) are also highlights. The weakest link, alas, is the actor playing Murphy/Robocop. When he's in the suit with the visor down, he works just fine, but since this version has him spending far more time with his face visible and his "humanity" present, it becomes painfully clear how welcome an actor with the charisma and eccentricity of Peter Weller would've been.

In the end, Robocop is a decent enough remake. I would buy it for a dollar, but I'd still buy the original at any price.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)